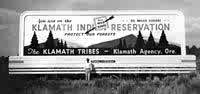

| Your land, my land? (Note from BH: The Herald & News ran a five-part series about the Klamath Tribes, their Reservation, Termination, Restoration, and their quest to get their land back. This is Part One. The other four parts follow below, in order. This information and much more that you need to know about the ESA, the Klamath Basin, and private property rights can be found at The Klamath Bucket Brigade's website -- http://www.klamathbucketbrigade.org/ -- please visit today.) June 19, 2005 By Dylan Darling [email protected] H & N Staff Writer Klamath Falls Herald & News P.O. Box 788 Klamath Falls, Oregon 97601-0320 541-885-4410 Fax: 541-883-4007 http://www.heraldandnews.com To submit a Letter to the Editor: [email protected] Before European-Americans began settling in Southern Oregon, Klamath, Modoc and Yahooskin Indians roamed over some 22 million acres, an area spanning from the upper reaches of the Sprague and Williamson rivers down to Mount Shasta in Northern California. The Klamath and Modoc tribes were familiar with each other, lived near each other, spoke similar languages and even had some overlapping territory. The Yahooskins were different -- part of a larger group called Snake Indians by white explorers because of the hissing sound of their language. In 1864, the United States government signed a treaty with the three groups that established a single reservation on 2 million acres of what is now central Klamath and Lake counties. The 2-million-acre reservation's boundary was made by tracing a line from mountaintop to mountain along the peaks that ring the upper Klamath Basin, giving the boundary the name "peak to peak." The reservation snugged up to the east side of Crater Lake, and most of Upper Klamath Lake was within its boundary. Over the following decades, surveys, changes in boundaries and land cessions reduced the size of the reservation to the 1.2 million acres it encompassed in 1954, when the federal government terminated the tribe and began the process of abolishing the reservation. Per capita payments Before termination, the federal government administered timber sales from reservation lands, with a portion of the proceeds going to each member of the Tribe. The disbursement of money to each member was called a "per capita" payment. By the time of termination in 1954, many of the members had come to depend on the per capita payments as their primary source of income. Although the payments put money in the pockets of the members of the Tribe, some members said the payments ended up weighing them down. "They knew that the per capita payments were coming in regularly, so what the heck, why would you work when that kind of situation is at hand?" said Andy Ortis, a member of the Klamath Tribe, who was sixteen at the time of termination and whose mother and grandmother passed records on to him. Tribal members were both undereducated and overdependent on their per capita payments, according to Theodore Stern, a scholar whose 1966 book "The Klamath Tribe: A People and Their Reservation" tells part of the Tribe history.  An unidentified man stands in front of a billboard welcoming visitors to the Klamath Indian Reservation. The photo was taken between 1942 and 1945. In the fifteen years before termination, each member on the Tribe's roll was getting about $800 per year. When totaled up for a family of four, that was more than the median income for the population as a whole in Klamath County at the time. Getting the checks every few months had a social impact as well as an economic impact on the Tribe. "There was little incentive to work to supplement timber revenues," Stern wrote. Tribal members also came to have negative views of public education, based on personal experiences and the stories of relatives who attended Indian schools, according to Stern, who is now retired in Los Angeles. The low opinion many members of the Tribe had of western education was forged in the federal Indian boarding schools. In the early 1900s, children from the Tribe were shipped away from their homes and boarded at schools at the Klamath Agency, Yainax Agency and Beatty. Many of the members had bad experiences in the boarding schools and passed their dislike and distrust on to the younger generations. "The schools ... offered little incentive to children who were convinced that a ceaseless flow of per capita dividends gave them an assured income for life," Stern wrote. While tribal members on the reservation suffered from a variety of social problems, the Tribes had something the federal government wanted -- almost a million acres of productive timberland. Even after years of logging, the ponderosa pine stands on the Klamath Reservation were thick with valuable timber. But tribal members had little input on their management. The Bureau of Indian Affairs determined when and where the trees were cut, with a portion of the proceeds being doled out to the members of the Tribes. The reservation's superintendent, who with one exception had always been a white man, had complete authority. Tribal members had to ask him about almost every major decision, including whether they could leave the reservation. "They treated us like children and dictated to our people," said Joe Hobbes, current vice chairman of the Klamath Tribes. Discontent As early as the 1920s, the tribal groups who had lived more than a half century on the Klamath Indian Reservation wanted out. They wanted out from under federal control. They wanted out of the reservation system. They wanted to control their own destiny. But there was disagreement over how to make it happen. Ideas ranged from selling the land and divvying the cash among individual members to creating a timber corporation run by the Tribes. By the 1930s, two leaders emerged with different visions of how to begin a life free of federal control in the 1930s: Wade Crawford and Boyd Jackson. Contention between the two men continued for years while the federal government considered methods for assimilating Indian people into mainstream culture. At least once in course of their debates, Crawford and Jackson ended up swapping stances on what would be the best course of action, and at one point came to a rare agreement. Crawford was the only tribal member to ever hold the position of superintendent of the Klamath Indian Reservation. Crawford took the job in 1933, but was removed by federal officials in 1937 because he hadn't been able to work with the factions among the Tribe. Some scholars speculate that he was bitter about that, fueling his desire for termination. Crawford wanted the Tribe to end its relationship with the federal government and become its own corporation. When that idea didn't pan out, he supported a buyout program in which tribal members could sell their interest in the reservation to the government for cash payments -- an early notion of what termination would eventually become. In his view, tribal members could use the money to start their own businesses. While Crawford called for tribal incorporation, Jackson proposed that the reservation be divided up and its pieces given to the individual members of the Tribes. Later, he and others called for the reservation to be held as a tribal asset, but not as a corporation. In a development that confused tribal members, the two agreed in late 1953 on the idea of a tribal cooperative taking over control of the reservation once federal supervision ended. But then Jackson changed his mind, and voted against the idea at a meeting of the Tribe's general council, according to Patrick Haynal, who wrote a doctoral thesis at the University of Oregon about the termination of the Tribes. While Crawford and Jackson, and their respective followers, debated, momentum was building nationally for terminating Indian tribes. Crawford went to Washington, D.C., in 1945 to push a liquidation bill, under which all jointly held tribal assets would be sold and money distributed to the members. The bill didn't pass, but the federal officials latched on to the idea of terminating the Klamath Tribes because they seemed ready for it, Haynal said. Termination pursued Congress had already been talking about using termination as a way to fully accomplish the assimilation of Indians into society, which began with the Dawes Act of 1887. The act provided for allotment of reservation land to individual Indians, making the lands eventually available on the open market and the American Indians subject to the laws of the federal government. Under the Dawes Act, officially called the General Land Allotment Act, Indian reservations were reduced in size while more land was opened up to settlement through the allotment of land in trust to individual Indians. In taking a piece of the reservation, the individual tribal member gave up regular payments that came from the selling of pooled resources on the reservation, such as timber on the Klamath Reservation. By the 1950s, the Klamath Reservation had been whittled to about 1.2 million acres through the revision of boundaries by the federal government and the allotment of land to individuals. In 1953, House Concurrent Resolution 108 called for an end of federal supervision and control for all the tribes of California, Florida, New York and Texas as soon as possible. Beyond those, it named five tribes that should be terminated -- one was the Klamath Tribe. Bureau of Indian Affairs officials and political activists told Congress that the Klamath Tribe were practically assimilated already and were ready for the government to get out of their affairs. The Tribes were considered ready for termination mostly because of their timber assets and their potential to be financially independent. One of the strongest backers of termination was Republican Sen. Arthur V. Watkins of Utah. He led the push for Resolution 108, and he then began the call for more legislation to bring about the termination of tribes across the country, including the Klamath Tribes, BIA officials said. Watkins was "bull-headed, wouldn't take no for answer" in his determination to get termination accomplished, according to Charles Wilkinson, an Indian law scholar who represented some members of the Klamath Tribe, and is now a professor at the University of Colorado in Boulder. The push for termination alarmed many Indians, Wilkinson said. Although some tribes had been calling for the end of federal supervision, they had to scramble to prepare for the sweeping changes that Watkins wanted to enact. The Klamath Tribe and the Menomonee Tribe of Wisconsin were the first tribes to be terminated, both in 1954. They rode the crest of a wave of 12 termination bills that by 1962 would eliminate 61 bands and tribes. The Klamath Tribe was a target for termination because of its success under federal control. It was one of the wealthiest tribes in the country, with the receipts from timber sales that generated payments to each tribal member. While the Klamath Tribe included Indians from three ethnic groups, the 2,133 members were bound by a common fate. They were going to be given an option by the federal government: Withdraw from the Tribe and get a cash payment, or remain and have whatever is left of the reservation held in trust by a bank. Timeline of Klamath Tribe's early history 1826 - The first contact between Europeans and Klamath Indians comes when explorer Peter Skene Ogden traverses the region. 1852 - Ben Wright, a local "Indian hunter" on the Applegate Trail, leads an ambush on Modoc Indians during a parley. His group kills 52 men, women and children, estimated to be about 10 percent of the entire Modoc population. October 14, 1864 - The federal government signs a treaty with the Klamath Tribe. The treaty applies to the Klamath, Modoc and Yahooskin bands. In the treaty, the Tribe cedes 20 million acres of territory to the United States, while retaining 2.2 million acres for a reservation. The treaty provides hunting, fishing and gathering rights in perpetuity. 1870 - A sawmill is completed to provide lumber for construction of the Klamath Tribal Agency. 1870 - A group of Modoc Indians leave the Klamath Reservation to return to their homelands near Tulelake. 1871 - The Tribe's reservation is reduced in size when a government survey excludes large parcels tribal land. June 1, 1873 - Modoc war leader Kientpoos, also known as Captain Jack, surrenders after leading the Modoc Indian War. The war lasted for six months. 1896 - A federal boundary commission says 617,000 acres had been excluded from the reservation in previous government surveys. The commission values the land at 83 cents per acre. 1896 - The sale of processed lumber from the reservation reaches a quarter-million board feet per year. 1901 - The United States pays the Tribe $537,007 for 621,824 acres. Twice the Tribe tries to get more payment, but fails both times. 1933-1937 - Wade Crawford, a member of the Klamath Tribe, serves as superintendent of the reservation, the only American Indian to serve at the post. 1945 - Crawford goes to Washington, D.C., to endorse a bill that would liquidate the Tribes. Sources: Klamath Tribes, National Park Service. Copyright 2005, Herald & News. http://www.heraldandnews.com/articles/2005/06/19/breaking_news/breaking1.txt http://www.klamathbucketbrigade.org/H&N's_Yourlandmyland062005.htm ===== A tribe vanishes - Proverbial stroke of pen terminates the Klamath Indian Tribe June 20, 2005 Second of five parts. By Dylan Darling [email protected] H & N Staff Writer Klamath Falls Herald & News P.O. Box 788 Klamath Falls, Oregon 97601-0320 541-885-4410 Fax: 541-883-4007 http://www.heraldandnews.com To submit a Letter to the Editor: [email protected]  A pine snag frames the Williamson River Valley in the heart of the former Klamath Indian Reservation. Tribal leaders today say the members of the Tribe were not adequately informed about the issue when they were asked to vote on liquidation of the reservation in 1958. It was called Public Law 587, and was enacted August 13, 1954, with the signature of President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Termination. The measure ended the federal supervision of the Klamath Tribe, which had been governed by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs since its leaders signed a treaty with the United States in 1864. It also opened the door to the federal government abolishing the 1.2-million-acre Klamath Indian Reservation in central Klamath and Lake counties. Even after the law was signed, termination wasn't immediate. As the government prepared to implement the law, it set a termination date of August 13, 1958, for the Klamath Tribe. But the process was more complicated than expected, pushing back the actual termination date to 1961. To guide the process, a three-man panel of management specialists -- Thomas B. Watters of Klamath Falls, William T. Phillips of Salem and Eugene G. Favell of Lakeview -- was appointed by Interior Secretary Douglas McKay. The specialists were paid $1,000 per month. The specialists commissioned a report by Stanford University researchers to study whether the Tribe was ready for termination. Contrary to previous studies, it said the Tribe was not ready. The trio also held many meetings in Klamath County and Washington, D.C., about termination. Their work led to many amendments to Public Law 587, designed to lessen the impact of termination to members of the Tribe and others in the county. One of the panel's recommendations was to not let all reservation lands go into commercial ownership because it would cause a glut of lumber on the market and depress the economy. The three specialists recommended that the reservation land be managed on a sustained-yield basis. Only large operators and federal agencies could afford the sustained-yield practice in the relatively slow-growing ponderosa pine forests on the reservation, so the specialists recommended that the federal government purchase the land. Termination became complete on April 17, 1961. The federal government purchased most of the Klamath Indian Reservation, converting it to a national forest named for tribal woman Toby Riddle, also known as Winema. She had served as a translator between government officials and war leader Captain Jack during the Modoc Indian War of 1872-73. Congress terminated the Klamath Tribe to give its members something they wanted, freedom from the oversight of the federal government. But termination also took away something that many tribal members later said they never wanted to give up -- their land. Ill-prepared to vote Arguments abound as to whether the members of the Tribe understood what was going on. Some say they understood what termination meant. Others say they were confused and thought they were just selling their timber and not their land. Before termination, Bureau of Indian Affairs officials and political activists who wanted Indians to be freed from the bonds of federal paternalism had told members of Congress that timber wealth made the Klamath Tribe ripe for termination. They said the Tribe could support itself on its own timber money. For decades, the members of the Tribe had received "per capita" payments, or individual shares of the proceeds from tribal timber sales. By 1954 those per capita payments were about $800 per year. The timber sales were a cash cow for the Tribe. Reservation forests had one-forth of commercial lands in Klamath County, according to the reservation's forest and agriculture officials quoted in the Herald and News on May 6, 1955. The officials said in the more than 42 years of logging on the reservation the average cut per year was 111 million board feet for a gross return of $32.75 million. In 1956, two years after Congress approved termination, the Stanford researchers found that the Tribe wasn't ready for termination, economically or socially, and that taking away the Tribe's land would devastate its members. The researchers said the reservation forest would have to be liquidated to pay withdrawing members of the tribes, and they said this wouldn't be in the best interest of tribal members, the regional economy or the nation. They said the members of the Tribes weren't prepared for the economic and social change. Despite the warnings of the Stanford report, the federal government proceeded with termination. When the time came to liquidate the reservation that was in large part covered with valuable pine timber, each tribal member was presented with two choices: 1. Withdraw from the Klamath Tribe and receive a one-time cash payout in exchange for an interest in the reservation. Those who selected this option came to be known as "withdrawing members." 2. Remain in the Tribe, with his or her share of the reservation managed by a yet-to-be-named institution. Those who selected this option came to be known as "remaining members." The Herald and News was unable to locate a copy of the mail-in ballots issued to tribal members. But it did obtain a ballot issued to adults voting on the behalf of children. The wording on the ballots was anything but easy for tribal members to understand, particularly because many lacked reading skills, said Andy Ortis, a member of the Klamath Tribe who was sixteen at the time of termination, and whose mother and grandmother passed records on to him. Following are the two choices on the ballot for someone voting for a minor or incompetent adult: "A. I elect for the member to remain in the tribe and have his share of tribal assets placed under a management plan substantially in the form of the plan dated February 1958, of which I have received a summary which is satisfactory as to form and content. "B. I elect for the member to withdraw from the tribe and to have the member's share of tribal assets converted into cash." In an explanatory material that came with the ballot, the appraised value of the reservation was set at about $159 million, and each member on the final roll of 2,133 people was entitled to an equal share in the tribal property. Officials at the time estimated that 70 percent of the members of the Tribes would choose to withdraw. The material explained the options as follows: "If you decide to withdraw, then: "a) Your share of the tribal property, based on its full appraised value, will be put up for sale. If the sale is for a price equal to the estimated realization value, you will receive approximately $58,650. If the sale is for a lower or higher price, you will receive the price received from the sale. Any payment to you will be reduced by your share of the tribal expenses. "b) Full payment will be made by August 13, 1960. "If you elect to remain in the tribe, then: "a) Your share of the tribal property will not be sold, but will be placed in the control of a trust company that will manage the forest lands on sustained yield principles, according to a Tribal Management Plan. "b) You may expect to receive about $1,050 each year for the next five years and about $880 each year there after." There was confusion, and scholars have said many tribal members didn't understand the consequences of withdrawing. And because no specific trustee was identified at the time of voting, many were leery of the option of remaining as members. Quick cash For many, the choice came down to getting a lot of money right away, or continuing to get regular payments, but with a mix of uncertainty and a continuation of control by another person. Most opted out of the Tribe. Of the 2,133 members of the Tribe on the final roll, 1,658 voted to withdraw and 77 elected to remain, while 398 didn't vote in May 1958. Those who did not vote were added to the list of remaining members, except for Edison Chiloquin, who began a lengthy battle to get his own parcel of land instead of continuing to get per capita payments. Those who withdrew from the Tribe got about $43,000. In all, about $70 million was paid out in 1961. The final individual payout to the withdrawing members was less than originally expected, in part to pay back outstanding loans and irrigation charges owed to the federal government were also subtracted from the final payout. Children born to members of the Tribe, either withdrawing or remaining, after August 13, 1954, didn't get any form of payment or stake in any trust. Minors on the final roll, whose parent or guardian had voted for them, didn't get the money directly. Individual trusts were set up and managed by attorneys. Many of the people who voted in 1958 have died. Still surviving are those who had others decide for them when there were minors, and the descendants of those who voted. One of the surviving voters is Chuck Kimbol, who later led lawsuits to regain hunting and fishing rights and then the push for restoration. He was 20 years old and just-married when it was time to vote. He decided to withdraw so he could have some money to start his new life. But he said many of those who voted to withdraw didn't understand what the result was going to be. "There were so many of them who didn't realize that the land was going with the timber," Kimbol said. The release of the termination money in 1961 started a flurry of spending by withdrawing members of the Tribe. "The most natural reaction is you are going to buy things you never had," Kimbol said. Daryl Ortis, brother of Andy Ortis and a rancher in the Sprague River Valley, was five years old when it was time to vote. His parents made his choice for him. They decided to remain. To explain why, Ortis' father gave him a dollar bill after a tribal meeting. Back then, $1 dollar had more buying power than today. Ortis said he went to the general store and bought bubble gum, Popsicles, licorice and more. He also saved 25 cents. The next day, his father told him he would give him $10 if he would give up his $1. Ortis told his father he had already spent most of it. "He said, 'That is what people do when they get money; they spend it foolishly,' '' Ortis said. His dad told him not to be enticed by the offer of big money, when having the reservation land and the per capita payments it provided was more valuable in the long run. "If you have something, cherish it," he said. "If it feeds you and takes care of you, take care of it." Evidence suggests few of the withdrawing members exercised such restraint. Copyright 2005, Herald & News. http://www.heraldandnews.com/articles/2005/06/20/news/top_stories/top2.txt http://www.klamathbucketbrigade.org/H&N's_Atribevanishes062105.htm ===== Spending Spree - Many Tribal members traded their interest in reservation for cash June 20, 2005 Third of five parts. By Dylan Darling [email protected] H & N Staff Writer Klamath Falls Herald & News P.O. Box 788 Klamath Falls, Oregon 97601-0320 541-885-4410 Fax: 541-883-4007 http://www.heraldandnews.com To submit a Letter to the Editor: [email protected] What would you do if you were presented with a check for quarter-million dollars? What for many is a daydream was reality for the more than 1,600 "withdrawing" members of the Klamath Tribe in 1961. Each of the members who had voted to withdraw from the tribe and receive a cash payout for their share of the reservation received a check for $43,124.71. Adjusted for inflation, that would be worth more than $276,600 today, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor's inflation calculator. The checks came from the federal government, which purchased most of the tribe's 1.2 million acres of reservation land. The money didn't last long. "They spent it everywhere," said Glen Kircher, who had started a hardware store in Chiloquin with his uncle in 1954. "I'm sure the businessmen in Chiloquin, Klamath Falls and around, liked to see the infusion of cash."  Clarence "Boonie" Jenkins was a child when he received a payment for his share of the former Klamath Indian Reservation. He says many tribal members were ill-prepared to manage their money effectively. Many of his customers paid off debts and bought something they had always wanted. Some purchased houses or land and others invested in stocks or education. "And some threw their money away -- partying," Kircher said. Clarence "Boonie" Jenkins, a member of the Klamath Tribes who graduated from Klamath Union High School in 1961 after growing up in Chiloquin and Klamath Falls, said he saw many members of the Tribe go through their money fast, buying new cars, expensive appliances and other big-ticket items. "If you go back, the root of the thing is these people were getting $100 per month," Jenkins said. "If you give someone $43,000, hell yeah, they are going to buy a new car ... The new car dealers were in hog heaven because everyone had two or three." Many who had lived modest lives suddenly had the means to buy almost anything they wanted. "I know some of the Indians here, they would wear their clothes one time, then throw them away," Jenkins said. Jenkins was a minor when the payments to the members of the Tribe were made, so his money was held in trust by an attorney, or trust officer. Even after he turned eighteen, he still had to go to the attorney to get to his money, he said. And each time he took some out of the trust the attorney would charge an exorbitant fee. Jenkins used some of his money, along with money he earned by logging, to buy two Corvettes, a boat and room full of electric guitar equipment. He had a sizable amount left he wanted to invest, but his trust officer wouldn't let him take the money out when he told him about his plans. Then his parents came to him with some plans of their own. They had found a bowling alley for sale in Albany for $250,000, and needed some help with the down payment. He said he thought it was a great idea, because they were avid bowlers and had experience running a bowling alley. He was able to get $20,000 for them and they turned in the down payment.  Bob Mezger served as the manager of timberlands held in trust by U.S. Bank for remaining members of the Klamath Tribe. Mezger said trust officials sought to manage the lands in a way that was best for tribal members. The next day they got a bill for $208,000, Jenkins said. His parents didn't know that along with the alley came the business's debt. They weren't able to cover the cost. They lost the money they had gathered up for the down payment, including Jenkins' $20,000. "It should have worked out good for them, but it didn't," Jenkins said. He said many of the member of the tribes who got termination checks simply didn't know what to do with that amount of money. Mistakes made range from bad business decisions to flat-out fast spending. Tales are still told today of withdrawing members going around with paper sacks full of money or pockets stuffed with bills, buying new cars as if they were toys and treating them as such, saving too little and spending too much on alcohol, and soon ending up broke. Many of those tales were compiled into a novel published in fall 2003 by Oregon writer Rick Steber. Steber grew up in Chiloquin, the town that was once the heart of the reservation, and was a high school freshman in 1961. He heard the stories and witnessed how the money was squandered. "I saw brand new refrigerators, washers and dryers sitting on [the] porches of shacks that didn't have electricity," he said. Out in a field, he said, he saw a brand new Lincoln Continental pulling an irrigation line. Cars were expendable for many of the suddenly wealthy withdrawing members of the Tribe. Instead of getting an oil change, tune up or fixing a flat tire, some tribal members would just get a new car. "It was an interesting period of time, for all the wrong reasons," Steber said. Hucksters were also selling items around Chiloquin and the former reservation land, such as aluminum siding that made worn-down homes shine, but only until it fell off, Steber said. And merchants in Klamath Falls and other nearby towns were offering "Indian prices," inflated from the regular price. "The Indians were squandering the money, just recklessly," Steber said. "The money went fast. There were a lot of people, local merchants and stuff, who were standing in line to take it." Victims of dishonesty Not all of the members of the Tribe spent their money quickly or lived dangerously. But even many of those who tried to spend their money wisely didn't escape harm. Lawyers from the Native American Rights Fund, a non-profit Indian legal services organization based in Boulder, Colorado, charged that merchants had exploited withdrawing members. In December 1972, Federal Trade Commission (FTC) officials from the Seattle regional office traveled to Klamath Falls to hold a public hearing. The FTC concluded that members of the Tribe were charged inflated prices for cars, homes and other items, compared to what white customers paid, sometimes double the cost or more. Many were also bamboozled by door-to-door salespeople who charged ridiculous prices for products with exaggerated benefits. One product was a vacuum [cleaner] that was "was the best in the world ... it had an activated charcoal air filter system ... and would prevent colds, cause sound sleep, and reduce air pollution," according to testimony at the hearing. FTC officials also looked into the dealings of trustees and lawyers who represented many of the withdrawing members of the Tribe. Of the 1,658 who opted to withdraw from the Klamath Tribe, almost 1,200 had their share held in a trust or guardianship. Many of these 1,200 had been minors at the time of termination. Reports abounded of trustees and lawyers abusing their privileges, taking money from their clients and charging exorbitant rates. One trust officer was reported to have charged $600 for photocopying costs to do an audit, according to the FTC report. "I think that we have sat back and rather expected the business people or lawyers, the bankers, the real estate agent to deal with us honestly because we feel they are in reputable business in a reputable community, supposedly, that they would deal fairly with us, and now we know better and we know that actually they do not deal with us honestly and fairly, and actually our money is more valuable to them than to us ..." Annabelle Bates, a withdrawn member of the Tribe said in testimony at the hearing. The FTC ended up recommending consumer counseling; coordination of federal, state and local consumer protection organizations; and funding of the non-profit group Organization of the Forgotten American, which is made up of remaining and withdrawing members of the former Klamath Tribe. The organization was formed in 1969 to represent interests of tribal members, at a time when there was no tribal structure. The organization is still in existence today. The FTC also recommended a study to see if any withdrawing members of the Tribe needed financial help from the federal government to get by. Meanwhile, the remaining members didn't need help with their finances. They continued to bring in annual checks reaped from the sale of timber still held in trust for them. Remaining members profit The financial winners after termination were the 474 members of the tribe who didn't immediately cash in their share of the reservation. In the 1960s and '70s, while many of the withdrawing members were spending away, the remaining members of the Tribe were still getting per-capita payments. Part of the reservation continued to be held in trust, administered by U.S. National Bank of Portland's Klamath Falls office. The bank was also known as U.S. Bank. The 474 ended up getting about $38,000 each from 1959 to 1974. The money came in the form of quarterly checks that ranged from $200 to $3,000, depending on the success of timber sales from 135,000 acres of land held in trust. The checks came from the Klamath Management Trust, which was run by U.S. Bank. Bob Mezger, who was the forest manager for U.S. Bank, said the goals of the bank paralleled the goals of the Tribe. "There was always a focus of what was best for the Indian owners," Mezger said. More than four decades after termination, the Klamath Tribes are still working to regain the former reservation the members refer to as their homeland. |