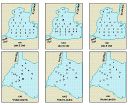

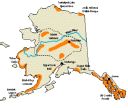

View image Go to the article Fig. 3. Alaskan habitats of special importance to geese. |

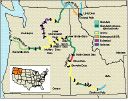

View image Go to the article Fig. 2. Location of important staging areas in western North America used by shorebirds during spring and fall migration. Size of dot indicates the estimated peak number of shorebirds at each site. |

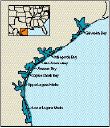

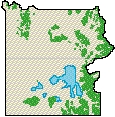

View image Go to the article Figure. Range of Mississippi sandhill cranes. |

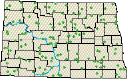

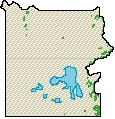

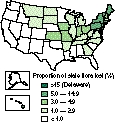

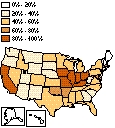

View image Go to the article Figure. Distribution of red-cockaded woodpeckers by county and state. Most historical RCW records are cited from Jackson 1971 and Hooper et al. 1980. For information on references, contact R. Costa. |

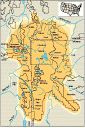

View image Go to the article Fig. 1. Approximate distribution of grizzly bears in 1850 compared to 1920 (a; Merriam 1922) and 1970-90 (b). Local extinction dates, by state, appear in (a). Populations identified in (b) are NCE -- North Cascades ecosystem, SE -- Selkirk ecosystem, CYE -- Cabinet-Yaak ecosystem, BE -- Bitterroot ecosystem, NCDE -- Northern Continental Divide ecosystem, GYE -- Greater Yellowstone ecosystem. As indicated in (b), a grizzly was killed in the San Juan Mountains of southern Colorado in 1979. |

View image Go to the article |

View image Go to the article Fig. 1. Range of the Indiana bat and locations of Priority 1 hibernacula (see text for definitions). |

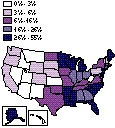

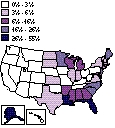

View image Go to the article Fig. 2. The harvest of antlered white-tailed deer (number per square mi or 259 ha of deer range) in 13 northeastern states in 1983 (first value) and in 1992 (second value); estimates for Virginia and West Virginia include young-of-the-year males (button bucks). |

View image Go to the article Fig. 1. Locations of survey areas for night-light counts of alligators in Florida, 1974-92. |

View image Go to the article Fig. 1. Historical and current distribution of the northern red-legged frog, California red-legged frog, and Cascades frog in California based on 2,068 museum records and 302 records from other sources. Dots indicate locality records based on verified museum specimens. Squares indicate locality records based on verified sightings (e.g., field notes, photographs, published papers). Red dots and green squares denote localities where native frogs are extant. Gold dots and blue squares indicate where native frogs are presumed extinct. Figure modified from Jennings and Hayes (1993). |

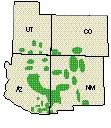

View image Go to the article Fig. 2. Historical and current distribution of the foothill yellow-legged frog, spotted frog, and Yavapai leopard frog in California based on 3,316 museum records and 171 records from other sources. Dots indicate locality records based on verified museum specimens. Squares indicate locality records based on verified sightings (e.g., field notes, photographs, published papers). Red dots and green squares denote localities where native frogs are extant. Gold dots and blue squares indicate where native frogs are presumed extinct. Figure modified from Jennings and Hayes (1993). |

View image Go to the article Fig. 3. Historical and current distribution of the mountain yellow-legged frog, and presumed native populations of the northern leopard frog in California based on 2,565 museum records and 673 records from other sources. Dots indicate locality records based on verified museum specimens. Squares indicate locality records based on verified sightings (e.g., field notes, photographs, published papers). Red dots and green squares denote localities where native frogs are extant. Gold dots and blue squares indicate where native frogs are presumed extinct. Figure modified from Jennings and Hayes (1993). |

View image Go to the article Fig. 1. Range of the Tarahumara frog, Rana tarahumarae. Copper smelters are at Douglas, AZ (now closed), and Cananea and Nacozari, Sonora. Historical locations include both surveyed populations that appeared stable, and unvisited historical localities (Campbell 1931; Little 1940; Williams 1960; Hale et al. 1977; Hale and May 1983; Hale and Jarchow 1988). |

View image Go to the article Fig. 1. U.S. range of the desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii). The six population segments for desert tortoises federally listed as threatened occur in parts of the Mojave and Colorado deserts that lie north and west of the Colorado River. |

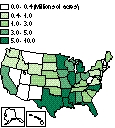

View image Go to the article Fig. 1. Total numbers of freshwater fishes and percentage imperiled by hydrographic region of the southeastern United States. |